The silver dragon is coiled around the trunk of a flowering plum tree, eyeing a pearl floating above milky mist suffused with shimmering ripples and eddies.

From what was once a few clods of lifeless steel, Sadatoshi Gassan has wrought a scene of striking detail and craftsmanship that just happens to adorn a 60-centimeter-long razor-sharp Japanese sword.

|

||||||||||

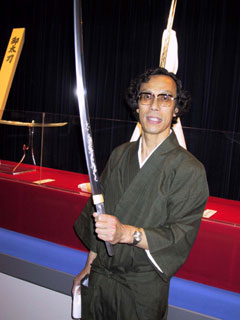

| Photo by Tim Hornyak |

The naked, curved blade in the ''katana'' style is one of about 20 works that the 54-year-old Nara Prefecture swordsmith is showing at a Tokyo department store. While the exhibition is likely to mainly draw collectors and dealers willing to pay up to 6.5 million yen for a Gassan weapon that does not include a fancy guard or scabbard, it offers a rare glimpse at contemporary Japanese swordmaking for the uninitiated.

''Everyday people can come to this show and realize that swords are a wonderful Japanese traditional art,'' said Gassan, one of about 80 smiths in Japan today who still make swords the old-fashioned way. ''I was born into a family that has traditionally made swords, and I want to preserve this tradition and pass it on to future generations.''

Gassan comes from a swordmaking lineage that goes back about 800 years to the Kamakura Period, when Buddhist monks in the ascetic Shugendo sect needed swords to protect their disciples on holy mountains such as the eponymous Mt. Gassan, one of the three Dewa Sanzan peaks in present-day Yamagata Prefecture, northern Japan.

In 1971, the government named his late father Sadaichi a Living National Treasure for his prowess in the ancient art, which he had learned from his own father. The current Gassan is the fifth generation of smiths since the Gassan school was relocated to Osaka around 1830.

Though Gassan hopes one day to be named a Living National Treasure like his father, he said he is chiefly concerned with producing outstanding blades that will last centuries.

''The Japanese sword is a marvelous heritage that is part of the true spirit of the Japanese people,'' he said. ''I want to carry on not only the techniques of the Gassan school, but other schools as well.''

The hallmark of his family's work is the ''ayasugi'' fabric of concentric grain lines forged into the steel that give the sword's surface a fine wood-like texture.

It is the result of a time- and labor-intensive process that involves repeatedly welding and folding sand steel into thousands of layers of iron with controlled carbon content. In addition to characteristic engravings, the blade is also given a unique temper pattern along the cutting edge that can resemble anything from clouds to flames or water.

Though he has the assistance of five young apprentices at his smithy in the city of Sakurai in Nara, it can take over one year for Gassan to make a sword. Even with Japan's depressed economy, Tokyo limits his annual output to about 10 swords, which makes it tough to recover the high production costs.

But Gassan says the most crucial element in trying to achieve perfection in the blades he makes, such as the ''tachi'' long sword and the dagger-like ''tanto,'' is ridding himself of such worldly concerns.

He is proud of the fact that his ancestors created blades for Japanese emperors, and he has made pieces now owned by New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where he and his father held an exhibition and swordmaking workshop in 1982.

Fame is part of the reason 26-year-old Gassan pupil Tsuyoshi Harada wants to pursue the craft. He currently works six days a week in the smithy under Gassan's strict tutelage, but will soon take an examination to become a smith himself.

''I don't know why, but I love swords,'' he said. ''Everyone thought I was crazy to get into it. Not having enough money is a minor problem compared to my goal of returning all the teachings my master has given me by exceeding him one day.''

Those who appreciate Japanese swords view them as works of art, not deadly weapons, said Kenichi Inami, whose Tokyo dealership Japan Sword helped organize the exhibition.

''I think it's the same as going to a great temple or shrine, or viewing fine paintings,'' said the 38-year-old Inami, adding his family-run business can still manage a profit even in times of moribund consumer spending and despite the shop's rarefied offerings -- he has one 13th-century blade for sale with a price tag of 35 million yen.

''This kind of business is very hard. Each swordsmith struggles to make a living, just like painters and other artists, but the swordmaking tradition is alive still in Japan.''